Talking Fungi: How a High School Grad Deciphers Plant Communication Like a Pro

Exploring Plant Communication in a Cutting-Edge Lab

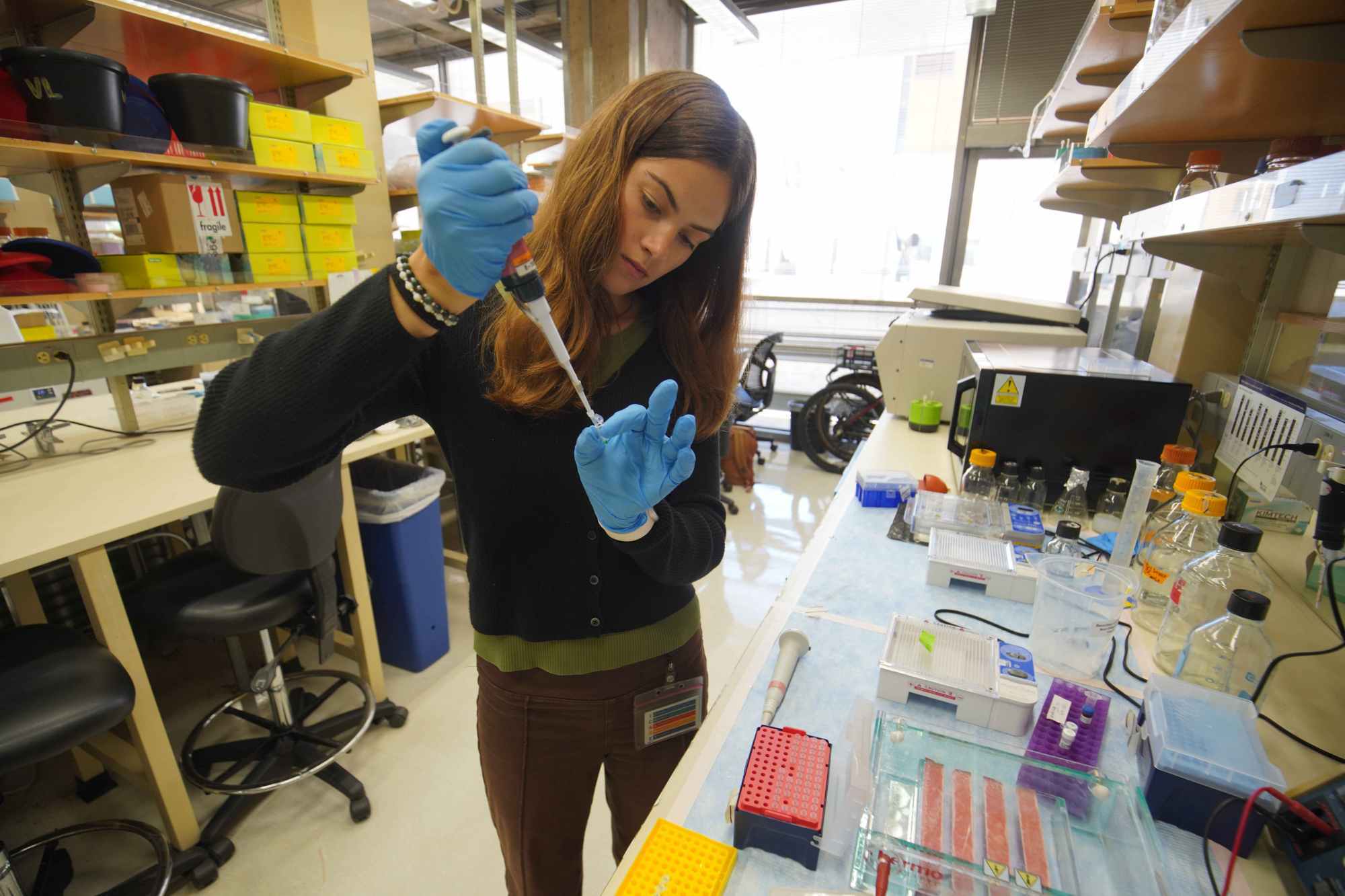

In Lena Mueller’s lab at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, dead plants are not a concern. Instead, they serve a purpose. Kelly Semtner, a high school intern working under Mueller, points to a row of wilted potted plants illuminated by ultraviolet LEDs. These plants have been harvested for seeds to conduct experiments on, all as part of a broader investigation into how plants communicate with one another.

The Salk Institute is a renowned research organization that explores a wide range of scientific disciplines, from neuroscience to plant chemistry. Mueller’s lab is located on the first floor of the campus and is filled with activity, advanced equipment, and numerous yellow Post-it notes that help keep the team organized.

Semtner is one of 13 interns participating in the Heithoff-Brody High School Summer Scholar Program, an eight-week paid initiative that includes a week of boot camp. This program has been running for over three decades and offers students a unique opportunity to engage in real-world scientific research. This year’s cohort will conclude this week.

With an acceptance rate of about 2.5%, the program is highly competitive. Semtner had to apply twice before being accepted. She was placed in Mueller’s lab under the mentorship of PhD candidate Sagar Bashyal, where she focuses on studying plant communication at the molecular level.

“It’s a really amazing program because it gives students actual hands-on experience,” said Mueller, who has been at Salk for about a year and a half. “They’re contributing to actual experiments and projects that we would be doing anyway.”

Many students don’t get the chance to work in such a complex lab setting until they are well into their college years, after completing advanced STEM courses like biochemistry, organic chemistry, cell biology, and genetics. Semtner, a recent graduate from High Tech High Mesa in Clairemont, will be attending UC Santa Barbara in the fall to study biology at the College of Creative Studies.

“Lab experience is so different from classes. It’s a whole different thing,” Semtner said. Her interest in the program was sparked by her high school biology teacher, Megan Patty. “It was a little intimidating from the outside, especially because Salk is so high-tech, but as soon as I got to meet people, it was much more welcoming.”

The Science Behind Plant-Fungi Relationships

Mueller’s research focuses on arbuscular mycorrhiza symbiosis, a long-standing partnership between plants and fungi that dates back 400 million years. These fungi live in the soil and colonize the roots of plants, helping them absorb nutrients in exchange for carbon from the plant.

“This is a very old process,” explained Mueller. “The fungi help with nutrient uptake, and they don’t do it for free. The plant returns carbon to the fungus.”

Mueller, who grew up in southern Germany and studied plant biology as an undergraduate in Zürich, didn’t start exploring fungi until her post-doctoral research at Cornell University. Since then, she has become deeply fascinated with this relationship. Semtner is only her second lab intern since joining Salk, and she is specifically focused on understanding the communication between plants and fungi.

For the symbiotic relationship to take place, plants must recognize the fungi as partners. “There’s some manipulation for new partners that goes on, but generally they’re talking to each other on good terms,” Mueller explained.

This process works somewhat like a dating app. Plants release chemical compounds and signals into the soil, acting as messages when something in the area, like a fungus, begins to approach. If it’s a match, tiny receptors on the surface of the fungus will receive that message, leading to a connection between the two.

A Focus on Molecular Communication

Semtner’s role throughout the summer has been to study how these signals and receptors function and what information they are conveying. The ultimate goal of Mueller’s research is to explore whether this fungal-plant relationship could potentially replace harmful pesticide treatments used in large-scale agriculture.

“I’ve been doing different lab work, mostly molecular,” said Semtner. “I’ve been measuring different receptors or peptides, or seeing the effects they have on plants.”

She noted that the researchers are aware that interns may not come in with a college-level background in biology, so they provide support and guidance. “To some degree, failure and messing up is definitely a part of science,” she said. She shared an experience where she lost an entire dataset due to a technical error and had to redo the work. “But otherwise, it’s been pretty good, knowing how to rebound from anything that’s not as you expected.”

Posting Komentar untuk "Talking Fungi: How a High School Grad Deciphers Plant Communication Like a Pro"

Posting Komentar