Talking Fungi: How a High School Graduate Deciphers Plant Communication

A Unique Opportunity for High School Students at the Salk Institute

In Lena Mueller’s lab at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, it’s perfectly normal to see plants that are no longer alive. These plants are not dead due to neglect or mishandling; rather, they have been intentionally harvested for seeds to support research on plant communication. This process is part of an ongoing effort to understand how plants interact with each other and their environment.

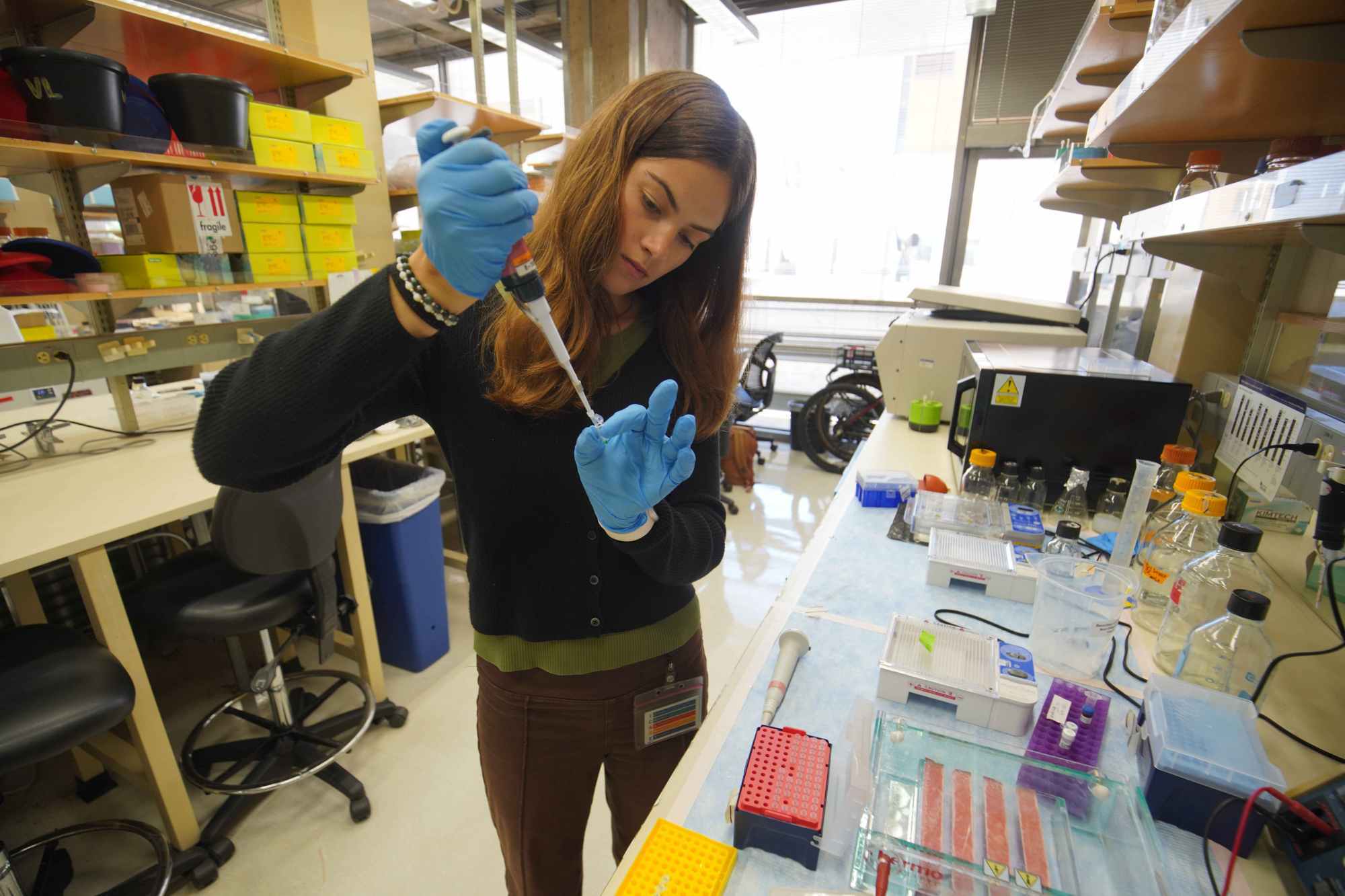

Kelly Semtner, a high school intern in Mueller’s lab, explains that the plants are being used for experiments that explore the complex ways in which plants communicate. “Don’t worry, it’s on purpose,” she says, pointing to a row of wilted potted plants illuminated by ultraviolet LEDs. The work being done here is far from routine, as it involves studying the molecular mechanisms behind plant-fungi relationships.

The Salk Institute is a renowned nonprofit organization dedicated to scientific research across various fields, including neuroscience, genetics, and plant biology. Mueller’s lab, located on the first floor of the campus, is filled with activity, advanced equipment, and countless yellow Post-It notes. It’s a hub of innovation where students and researchers collaborate on groundbreaking projects.

Semtner is one of 13 interns participating in the Heithoff-Brody High School Summer Scholar Program, a long-standing initiative that has provided students with hands-on experience in scientific research for over three decades. The program is highly competitive, with an acceptance rate of about 2.5%. This year, 521 students applied, and Semtner was among those selected after two attempts. She was placed in Mueller’s lab under the mentorship of PhD candidate Sagar Bashyal to study plant communication at the molecular level.

“This is a really amazing program because it gives students actual hands-on experience,” Mueller said. “They’re contributing to real experiments and projects that we would be doing anyway.” Many students don’t get the chance to engage in such complex laboratory work until they are well into their college years, having taken advanced STEM courses like biochemistry and genetics. Semtner, a recent graduate from High Tech High Mesa in Clairemont, will begin her studies at UC Santa Barbara in the fall, majoring in biology at the College of Creative Studies.

“Lab experience is so different from classes. It’s a whole different thing,” Semtner explained. Her interest in the program was sparked by her high school biology teacher, Megan Patty. “It was a little intimidating from the outside, especially because Salk is so high-tech, but as soon as I met people, it was much more welcoming.”

Mueller’s research focuses on arbuscular mycorrhiza symbiosis, a mutualistic relationship between plants and fungi that has existed for approximately 400 million years. In this partnership, fungi colonize the roots of plants, helping them absorb nutrients from the soil. In return, the plants provide the fungi with carbon. This ancient relationship is a key area of study for Mueller and her team.

Growing up in southern Germany, Mueller studied plant biology as an undergraduate in Zürich. She didn’t become deeply involved with fungi until her postdoctoral research at Cornell University, where her fascination with the subject took root. Semtner is only her second lab intern since joining Salk, and she is focused on understanding the signals and receptors that facilitate communication between plants and fungi.

For the symbiotic exchange to occur, plants must recognize the fungi as partners. “There’s some manipulation for new partners that goes on, but generally they’re talking to each other on good terms,” Mueller explained. This process is somewhat similar to a dating app: Plants release chemical compounds into the soil, acting as messages when a potential partner, like a fungus, approaches. If the signal is received, a connection is formed.

Semtner’s role in the summer has been to study these signals and receptors, aiming to uncover what information they convey. The ultimate goal of Mueller’s research is to determine if this natural fungal-plant relationship could one day replace harmful pesticide treatments used in agriculture.

“I’ve been doing different lab work, mostly molecular,” Semtner said. “I’ve been measuring different receptors or peptides, or seeing the effects they have on plants.” She admitted that the work can be challenging, but the researchers in the lab are aware that interns may not have a college-level background in biology. “To some degree, failure and messing up is definitely a part of science,” she said. She shared a story about losing an entire dataset due to a technical error, which required her to start over. “But otherwise, it’s been pretty good, knowing how to rebound from anything that’s not as you expected.”

Posting Komentar untuk "Talking Fungi: How a High School Graduate Deciphers Plant Communication"

Posting Komentar