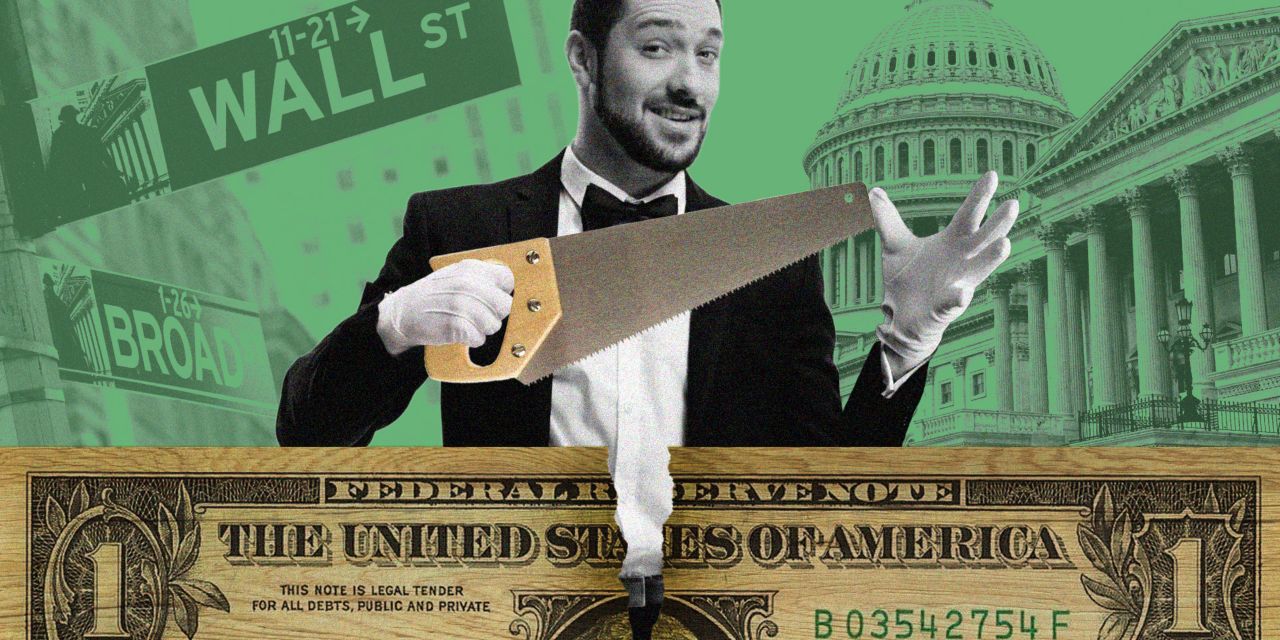

Only One Wins in This Treasury Bond Bet — And It's Not You

The Perils of Investing in Long-Term Treasury Bonds

There is a simple investing rule that should be followed: never catch a falling safe, especially when the government is dropping it. While there are times to buy bonds, it's not advisable when the U.S. budget deficit is reaching record levels and the Federal Reserve seems complicit in the situation. The 2055 zero-coupon Treasury bond has plummeted by two-thirds from its peak during the pandemic. Some investors see this as an opportunity, thinking that something down 66% must be oversold. However, history has shown that buying the dip can lead to regret.

These bonds are actually riskier than failed bank stocks. They represent 30-year IOUs from a government running $2 trillion deficits, which means you'll be repaid in dollars that may only buy half a ham sandwich. Lehman Bros. collapsed in a weekend, but these bonds are like financial suicide on an installment plan.

Let’s explore why today’s “bargain” could become tomorrow’s disaster. Zero-coupon bonds pay no interest until maturity. You purchase them at a discount and receive face value at the end. For example, the 2055 issue requires you to pay $24 now for $100 in 30 years. That's longer than many murder sentences or most marriages. It's like betting on the Jets to win the Super Bowl — at least with them, the suffering ends in January.

Duration Risk: The First Trap

The arithmetic behind these bonds is revealing. Paying about $24 today to get $100 in 2055 means these bonds are extremely sensitive to interest rate changes. With 30 years until maturity, a one percentage point increase in interest rates would drop your $24 bond to about $17 — a 30% loss instantly. Conversely, if rates fall by one point, it jumps to $31. These aren't investments but leveraged bets on interest rates.

Inflation: The Real Killer

Inflation is the real threat here. After 30 years, your $100 will buy what $13 buys today. The real trap lies in the future $100. Inflation isn't just about CPI prints; it's about monetary dilution. The U.S. money supply has grown at 7% annually for decades. At this rate, purchasing power halves every decade. After 30 years, your $100 will have the same value as $13 today.

In a taxable account, the IRS imputes phantom interest each year. This means you're taxed on gains while inflation erodes your investment's value. The bulls might cite historical examples, such as the early 1980s when long bonds paid double digits. But prices crashed first, then yields became genuine bargains. We are nowhere near that point.

The Government’s ‘Solution’

The Fed cuts rates like a drunk surgeon — quick, sloppy, and with complete confidence that this time will be different. The government's solution involves printing money to buy bonds, which is akin to paying your Visa with your Mastercard, except you own both cards plus the bank. This approach is supposed to make sense, but it doesn’t.

The Treasury floods the market with more IOUs, while Congress spends the freshly printed money on programs that are guaranteed to work this time. However, the situation is dire. The Treasury must sell $2 trillion in new bonds annually just to fund deficits. Foreign central banks that used to buy are now selling. The Fed can't buy without restarting inflation, leaving pension funds and banks drowning in underwater bonds.

Until deficits shrink or buyers magically appear, these bonds keep falling.

Wall Street’s Rescue Fantasies

When bonds crack, stocks follow. When the math doesn't add up, Wall Street reaches for miracles. This time, it's AI — the productivity fairy with a silicon wand — here to cure inflation and rescue these bonds. However, AI may cut costs at the factory, but policy adds fees, taxes, mandates, and compliance that eat the savings. If a robot makes your burger for two dollars, someone will find three reasons it should cost six at the register.

Deficits are not background noise; they are the soundtrack. A big primary deficit means a relentless auction calendar for Treasury. There is no magic buyer. The buyer is you, your pension, your bank, your insurer, or a foreign central bank with its own politics. Every one of them now demands a premium for inflation risk, fiscal risk, and policy risk. That premium is the term premium. It is not, if you own the long end, your friend.

What to Do If You Own These Bonds

Here’s what Wall Street doesn’t tell you: You’re not an investor; you’re the mark. If you're sitting on these zeros, you have three choices: hold and pray for a miracle, sell and take your loss, or double down because you enjoy pain.

If you insist on playing, at least watch who is buying. Strong demand from real investors means the market believes the story. Weak auctions that need Fed rescue tell you everything. When the government becomes its own best customer, you are not investing. You are enabling a system that must eventually reconcile with reality.

The Three Rules of Bond Buying

Here’s what Wall Street doesn’t tell you: that you’re not an investor; you’re the mark. The government is holding pocket aces. The Fed’s dealing from the bottom of the deck. The financial press is the shill who keeps saying the game is honest. And you? You’re the tourist from Ohio who just asked if a straight beats a flush.

So let me spell it out:

First rule of bonds: The house always wins.

Second rule of bonds: You’re not the house.

Third rule of bonds: See Rule 1.

Posting Komentar untuk "Only One Wins in This Treasury Bond Bet — And It's Not You"

Posting Komentar